AADHAR: THE NAMELESS DILEMMA

In rural Rajasthan, the first question one encounters is, ‘Aapki kya jaat hai?’ ( What is your caste? ) even before the question of name is taken into consideration. Caste is the first signifier of identity in rural India, but what if it becomes secondary to one’s name? In the earlier phase of my fellowship, I thought that caste was problematic as an identity. But in the coming months, I confronted a pernicious reality that surfaced and ramified the patriarchal subjugation in the form of an etymologically suppressive naming system for girls.

Annie Zaidi, in the introduction to her book Unbound, says that ‘Patriarchy is nothing if not domestic.’ Domestic life weaves the vicious cycle of patriarchy around women. We think that the ‘purdah’ is a kind of suppression that women face in the twenty-first century but rather what is actually questionable and needs to be addressed is the oblivious way in which this system keeps its web ever-growing.

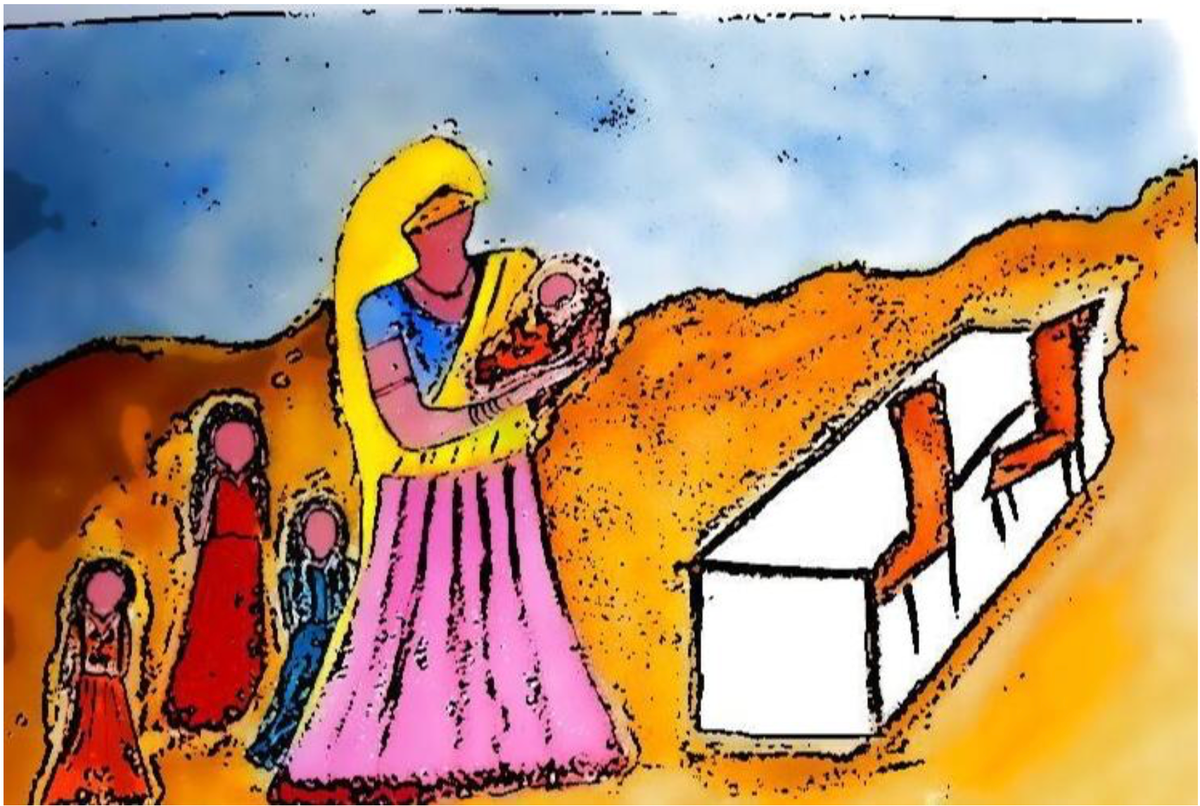

I had a shocking revelation on how women's condition remains unchanged. I attended a government camp in the village to help in the process of Aadhar registration. While I was helping the community fill out forms of Aadhar, when a woman - a mother of four - walked in, with three daughters standing next to her and one in her lap. She quickly gave me details of the three daughters, who didn't seem to have a lot of age gap between them, the oldest being four years old. When the youngest daughter’s turn came for registration, she was clueless, rather she asked me to suggest a ‘name’ for her daughter. The plea left me dumbfounded. I asked her again in reconfirmation if I heard her correct? She nodded in confirmation, asking me to give her a ‘suitable name.’ I felt mentally bogged about how a stranger could name anyone’s children. I experienced mixed emotions of resentment towards the system and pity towards the women when I tried to understand the situation.

Facts become more explicit if we place a hierarchy pyramid of three levels to understand the subjugation that Indian society subjects on women. At the bottom is one’s gender, then it's caste, and at the top its economy. Now supposedly, we place this woman and countless other women like her in this hierarchy, it shows that the patriarchal system suppresses them not only in terms of gender but also steals away their chance to climb up the socio-economic ladder. For example, a woman of lower caste with no income source makes her the worst victim of this systematic subjugation.

Arundhati Roy has rightly observed that ‘India, a country that lives in several centuries simultaneously.’ We still live in a society that seeks male heirs, and if girls are born they are never allowed to move up the socio-economic ladder, assuming that more independence may lead women astray. Names like Niraj meaning ‘unhappy,’ Dhapu meaning 'fed up with the birth of girls,’ Antima meaning ‘it may be the last of daughters to be born,’ Mafi meaning ‘feeling sorry for the birth of a daughter' and Ramghani meaning ‘a plea to Lord Ram to stop the birth of anymore daughters as they already had enough of them.’ These names are audacious of suppression, they need no exhaustive discourses to validify.

These women, under the garb of purdah, push to carry their 'faceless and nameless identity' irrespectively and have surrendered to fate: their minds consummated with patriarchal thinking, their bodies wailing in exhaustive desperation for a male heir. Each birth deepens the dilemma. They may lose or win this battle, still, no victory entitlements will be honored. They are bound to drag these etymologically suppressive titles from birth to death. The dilemma that these women face, hidden under their ‘purdah’ is contrary to what Aadhar guarantees to grant us - an identity.